In Guido Lengwiler’s book A History of Screen Printing: How an Art Evolved into an Industry, readers discover, page by page, reproductions of screenprints whose quality and style are strikingly similar to those of today. As early as the 20th century, California experienced another gold rush: the one that led artists to screen printing, a major medium of expression for graphic designers and illustrators.

Screen printing isn’t Chinese!

Although the screen printing technique may seem simple, manually created stencils continued to be used after World War II. Cost-effective and easy to handle, they remained present in art studios, where it is still common to see artists drawing or cutting their stencils by hand, then printing manually, in the great tradition of illuminators. However, what we now call screen printing is not limited to the use of stencils. Of course, the Chinese and Japanese have used paper stencils held in place with silk threads for centuries — as seen in the katagami technique — but without the use of a fine mesh, characteristic of modern screen printing, where the stencil is directly created on this mesh: the screen.

“References to ancient stencil techniques dating back to the 3rd millennium do not properly establish the conditions for the development of this process as we know it today.” (Siegfried Fuchs)

Old screens are sometimes so beautiful that they are even used for decoration. Altforliving. © Photo Scott Frances

In 1926, Hans Caspar Ulrich described the making of the screen printing stencil: “We still used Chinese ink to draw the design directly onto the stretched fabric. The unprinted areas were then blocked out with varnish. The process was slow, and the lines were not sharp. Alternatively, we cut adhesive paper and applied it to the gauze (the translucent fabric made of silk, linen, or cotton). But this method was not suitable for very fine patterns.”

Meanwhile, screen printing workshops gradually began to adopt the photographic process. A modern invention? Well, no: as early as 1906, the Frenchman Jehan Raymond filed a patent based on a process already described in 1892 by François Schreurs for textile printing. He was followed in 1907 by the Englishman Samuel Simon. Yet, it is Simon who appears in all the history books!

At that time, ready-to-use products did not yet exist. The high cost and complexity of the chemical formulas made this technique difficult to use. It wasn’t until 1917 that the photographic process became almost as simple as a photo print.

How does it work? A photosensitive emulsion is applied to the fabric, instead of paper. The design, drawn on a transparent film, is exposed to the emulsion, which “darkens” under the effect of light. Modern screen printing was born…

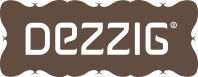

Screen-printed brochure (produced between 1940 and 1950) on the use of Nu-film and Blufilm, invented around 1937.

To simplify the creation of stencils, several inventions were developed, including transparent sheets coated with a transfer product. This sheet was placed over the drawing, and the transfer layer was “scraped” off to reveal the areas to be printed. The sheet was then applied to the screen to adhere the covering product, and the sheet was peeled off. Easy! This way, the fabric mesh was blocked, preventing jagged edges.

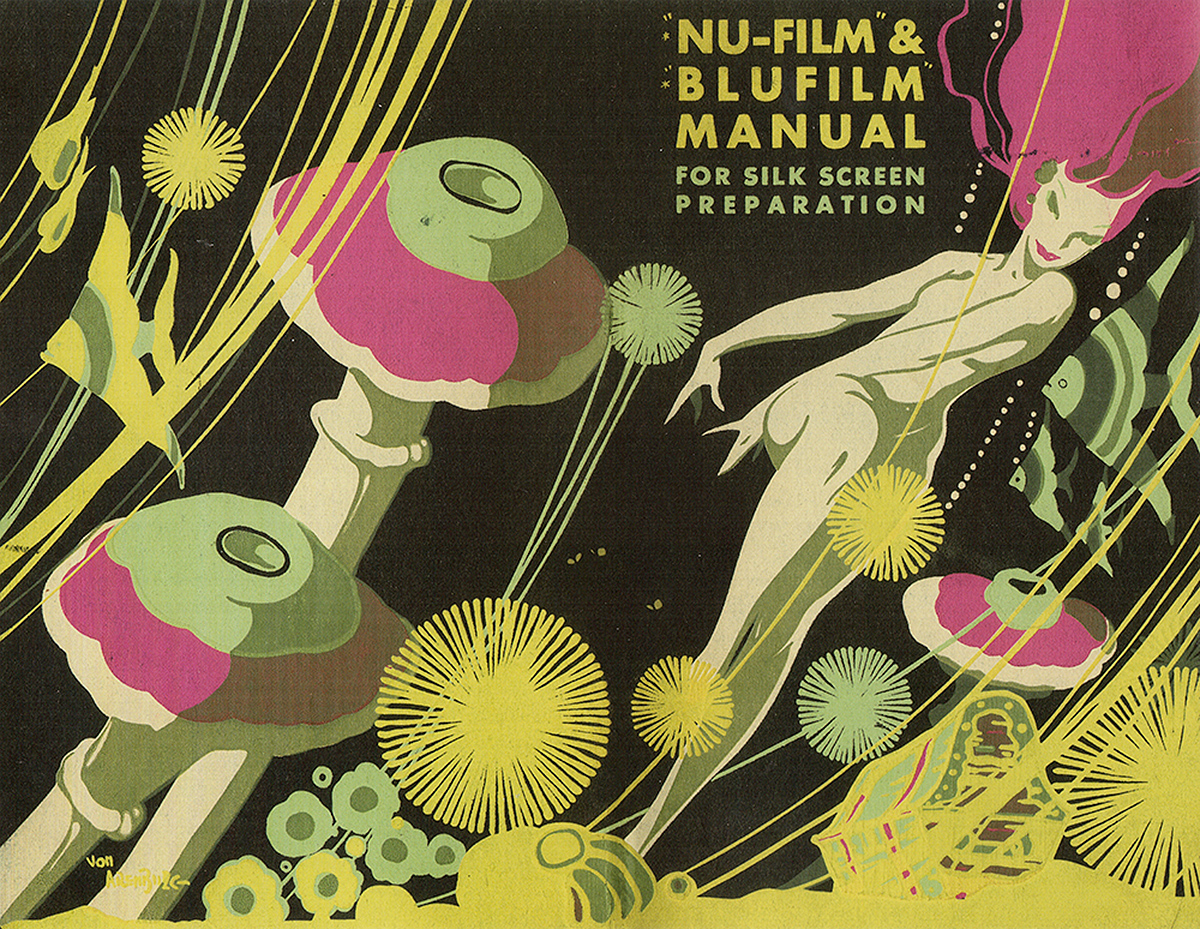

Screenprint by Vitachrome between 1923 and 1926 in 13 colors on wood support.

In 1923, screen printing was already making art

Unlike lithography, screen printing allows for layering inks and creating… texture! This feature quickly caught the attention of art dealers. In 1923, Young & McCallister launched fine art reproduction for the first time in Los Angeles, before founding the Vitachrome company: a golden age of screen printing.

At the time, no printing process could rival the vibrancy of the colors and the quality of their prints. Their reproductions of paintings would even directly compete with those produced through lithography.

Much more cost-effective for small print runs, screen printed formats are larger, and the materials more varied (cardboard, paper, glass, fabric): it’s a real success! The use of photographic stencils, combined with traditional hand-cut stencils, allows for the printing of artworks in 20 colors on paper. The prints were achieved through total or partial overlays, using thick, opaque inks (gouache) and even oil paint!

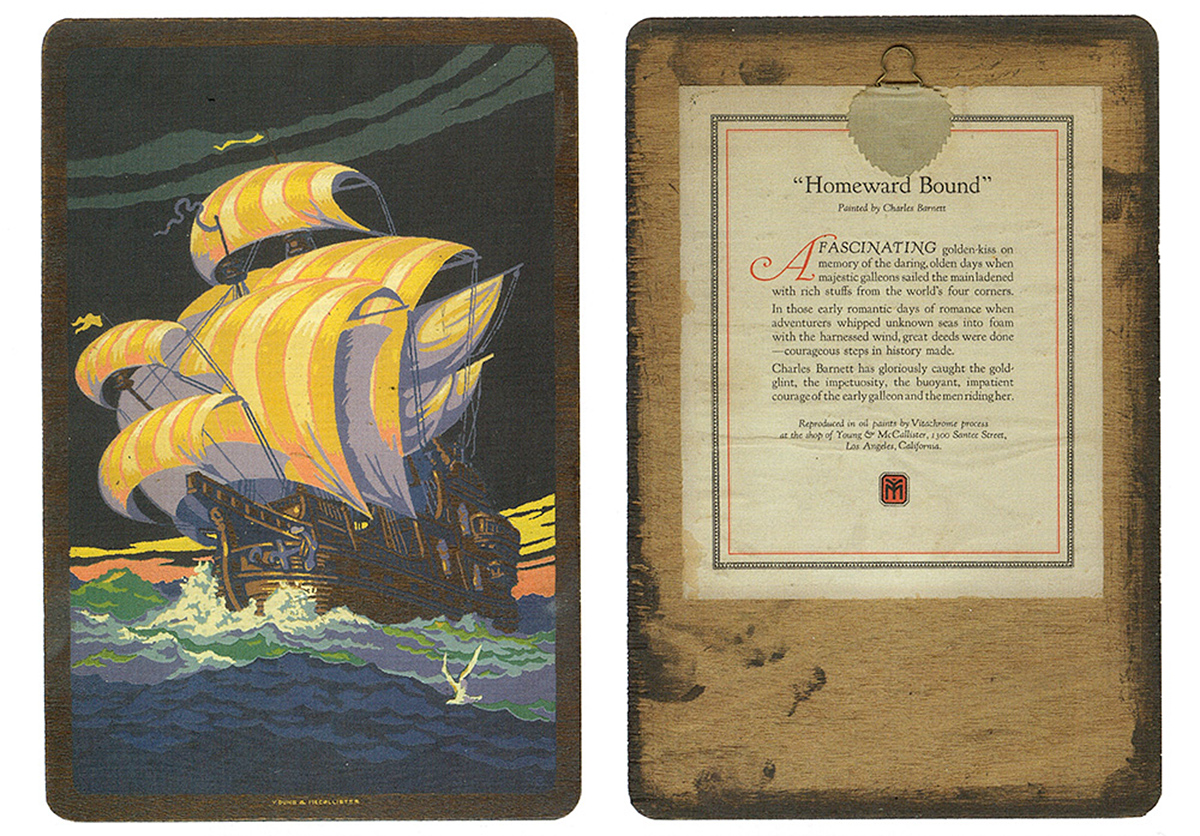

Art prints reproduced by screen printing by the Tongue-Art Company in 1923. Water-based inks / 30 color passes.

The Californian artist Gilbert Tongue was, in 1917, fascinated by the idea of reproducing fine art using screen printing. He would later become a master in art reproduction with the Tongue-Art Company. The quality level achieved was so high that some gouache prints in the 1920s could feature up to 30 colors! To describe these reproductions, he didn’t use the term silk screen print, but rather coined the term Sayrographics.

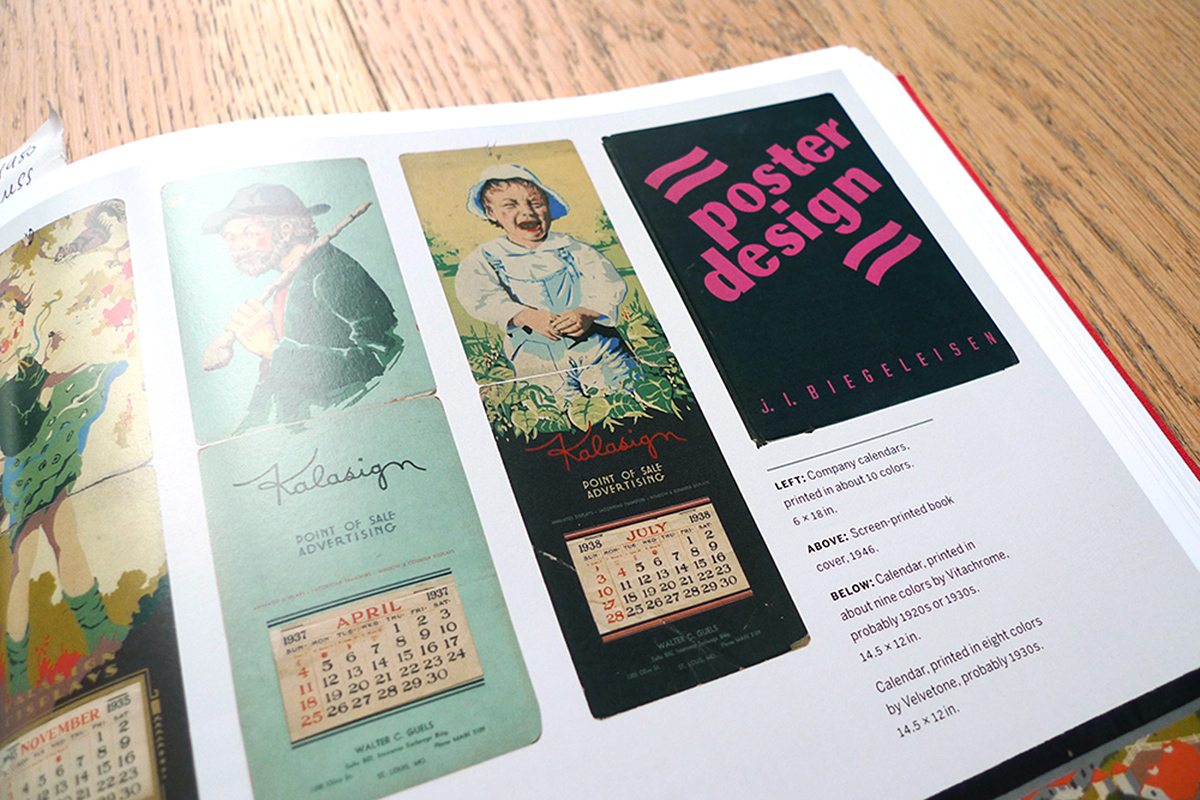

Screen printed calendars by Vitachrome and Velvetone between 1920 and 1930.

Screenprint for everyone!

Among the many press pages reproduced in Guido Lengwiler’s book, Signs of the Times (the national journal of visual advertising) was the first to report on the screen printing phenomenon starting in 1916, during World War I. Through his articles, William Hugh Gordon, a prominent American typographer, greatly contributed to the rise and spread of this technique worldwide.

The first screen printing schools were already established in New York in 1937.

If you thought the democratization of screen printing is recent… think again. In 1925, printing kits were already being distributed by Naz-Dar, a company from Chicago. “Easy to do, easy to learn.” This marks the beginning of the screen printing trend in the United States, and it seems incredibly easy: The silkscreen stencil reproduction method includes a complete kit to create stencils, a fabric screen, a squeegee, and various ink colors (oil- or water-based). Other ads, like those from Strongs in Detroit, even offered beginner kits and a full catalog of supplies as early as 1924. With screen printing, the artist prints their own work.

In the Signs of the Times magazine, Nazdar (Chicago) announced the first screen printing kits in 1925, while the first consumer manual would not be published until 1939.

The first manual Silk Screen Process Knowledge was written by Harry Leroy Hiett in 1922 (he is considered the founder of industrial screen printing). To read the first screen printing guide aimed at the general public, one would have to wait for the publication in 1939: Silk Screen Stencil Craft as a Hobby. An advertisement from the California School of Screen Process would later promise, in 1946, to double your income through the practice of screen printing.

Rosslyn, Virginia, 1926. “Walling Process Inc.” A graphics business owned by one George Walling. National Photo Co. Collection glass negative.

WPA Federal Art Project in New York in 1938, a period of intense creativity and modernity.

From silkscreen to serigraphy: art hits the deadlines

“I feel that the production of art needs a term more suitable than Silk Screen Process.” This is how American artist Anthony Velonis explains the birth of the term serigraphy in 1930.

In fact, the term Serigraph was coined by Carl Zigrosser, the curator of prints at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, during an exhibition of screen-printed works organized at the Weyhe Gallery in New York. The name Serigraph was then proposed as a designation to distinguish screen printing created by an artist (in the fine arts field) from those executed on an industrial scale.

At the very same time that screen printing was producing signs and advertisements, a portion of the production was intended for artistic works, often signed by the artist’s hand. The explosion of art screen printing took place during the Great Depression in the United States (between 1929 and 1933). President Roosevelt launched his famous New Deal. While most of the funds were allocated to the construction of roads or bridges, 1% would be dedicated to artistic creation!

Starting in 1935, the Federal Art Project (FAP) became the largest graphic creation space in the world: for 8 years, nearly 35,000 works, including 2 million posters, were produced. Most of them were made using screen printing: a goldmine for collectors!

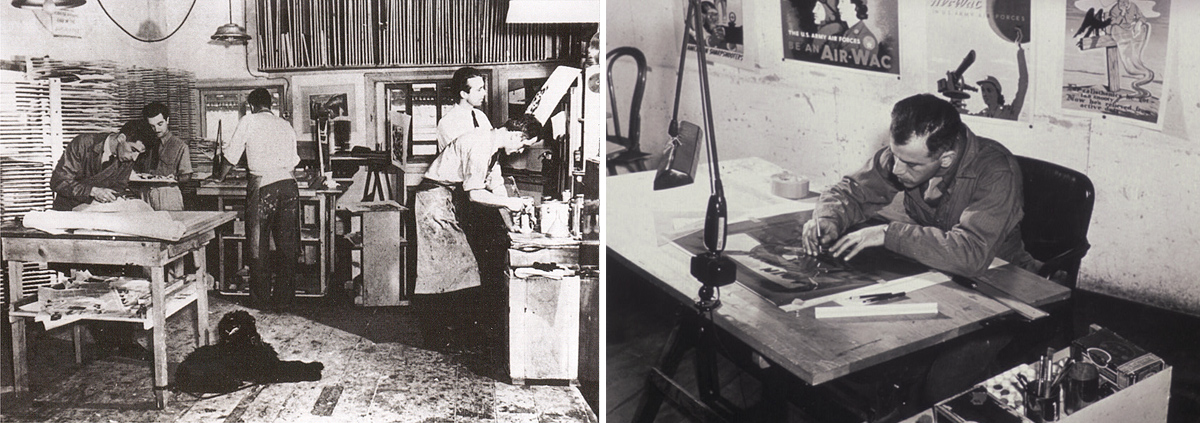

Anthony Velonis (on the right) in his screen printing studio. New York, 1939.

Poster created by Estelle Levine in 1936. Once Upon a Time poster by Kenneth Whitley. WPA posters. Work Projects Administration Poster Collection (Library of Congress).

In 1938, Anthony Velonis created the first silkscreen department of the FAP (Works Progress Administration – WPA). Trained early in this technique, and with the help of his team, he was able to produce 600 posters per day and manually print up to 8 colors. He conducted numerous demonstrations in schools and contributed to the spread of knowledge about silkscreen in the art world. In response to all the questions about the practice of art silkscreen, he published his first book, Technical Problems of the Artist, in 1938. Before this publication, artist Harry Gotlieb said about silkscreen: “I knew nothing about it, and no one knew anything, except for those who worked in advertising.”

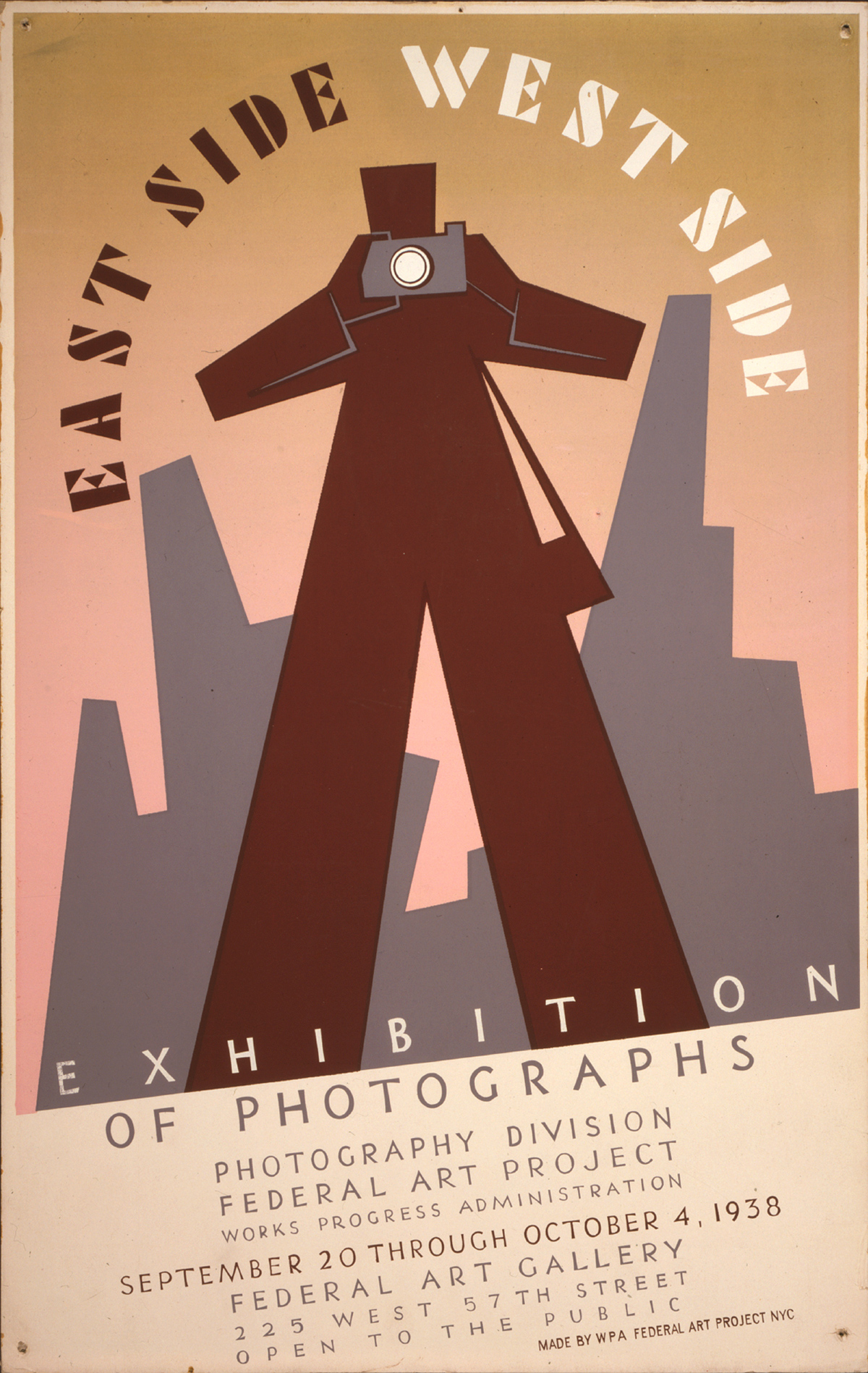

In the quantity of screen printed posters, a true style emerges: message effectiveness, typographic creation, and modern graphic language… Like most creations of the WPA, the posters all adopt the size of 14 inches (35.5 cm) by 22 inches (56 cm). These WPA Posters can be explored on the official website Rethinking WPA, where you can find works by Anthony Velonis, Foster Humfreville, Alex Kallenberg, Erik Hans Krause, Charles Verschuuren, and others.

East Side West Side Exhibition of Photographs par Anthony Velonis, New York City Federal Art Project, WPA, 1938. Silkscreen Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Today, what is the true value of a fine art screenprint? Whether advertising, industrial, or artistic, the printing technique is the same. This is what creates the most problematic confusion in the art market. For years, the terms serigraphy or serigraph would refer to a work created and manually printed. Today, the term printmaking is more widely used to identify prints made by hand or under the artist’s direction, signed and numbered.

Read on, Chapter 3:

The mysterious fate of art screen printing, 1940-1945

The translated excerpts and photographs from the book are reproduced with the permission of A History of Screen Printing: How an Art Evolved into an Industry

All rights reserved / Photos © 2014 Dezzig