Guido Lengwiler teaches screen printing at the School of Visual Arts in Bern and Biel (Switzerland). After 15 years of research across Europe and the United States, he published the much-anticipated book A History of Screen Printing, which I’ve previously discussed at length. This work uncovers a forgotten and previously untold chapter in the history of graphic arts. The interview was conducted by Uwe Heinisch.

Mr. Lengwiler, could you start by briefly telling us about your background and what led you to take an interest in screen printing? What is it about the process that particularly appeals to you?

With a touch of humor, you could say that screen printing was just a “detour” in my life — one that’s been going on for thirty years now! After completing my compulsory education, I went to the School of Applied Arts in Zurich, and a few years later, I joined Franz Fedier’s professional painting class in Basel. It was a wonderful time that opened my eyes to both classical and contemporary art.

During those years, I started printing my own graphic works in my small studio, initially using woodcut and photographic techniques. Then I came across a book that discussed the screen printing process, and I bought a wooden picture frame on which I stretched nylon fabric by hand. It was easy to build a simple system to hold the mesh and raise and lower it — no need for expensive presses like with other printing techniques of the time.

Printing was fascinating. Unfortunately, at that time, I was going through a tough period — I was heartbroken — and my emotional state was affecting my artistic work; I felt almost paralyzed. That’s when I decided to begin an apprenticeship in screen printing. Yes, indeed! A somewhat confusing professional journey, wouldn’t you say?

During my apprenticeship, and later at Fred Birchler’s in Zurich, we often printed cultural posters but also many other things, like textiles, tool cases, stickers, and more — at that time, screen printing was booming. The work required both thought and intuition, as the process and materials used were often very resistant! I believe this aspect of the work hasn’t changed today and continues to fascinate and inspire the younger generation just starting in this profession. Today, many graphic design and art students appreciate the opportunity to work with traditional printing inks alongside the world of Photoshop.

The 490-page screen printing book written by Guido Lengwiler traces the roots of fine art screen printing.

What motivated you to write a book on the history of screen printing? You couldn’t have done it for commercial reasons…

At first, there was no plan to write a book. Our research was progressing somewhat tentatively. The idea of a publication only came up after some time, when we realized that the material we had gathered was exceptional. I often discussed this with my brother, who works in the field of archiving.

Fortunately, we couldn’t foresee what lay ahead, because otherwise, I would never have ventured into a publishing project like this, if only for purely financial reasons! Books dealing with such specific cultural and historical topics are, for the most part, immediately associated with a loss-making venture with an uncertain future.

It was only thanks to the support of the screen printing industry that the publication became possible: CEO Christoph Tobler of Sefar offered his help, followed by Kissel+Wolf, the Eisenbeiss family, and several other companies in Europe and the United States. All of these people share the credit for our publication.

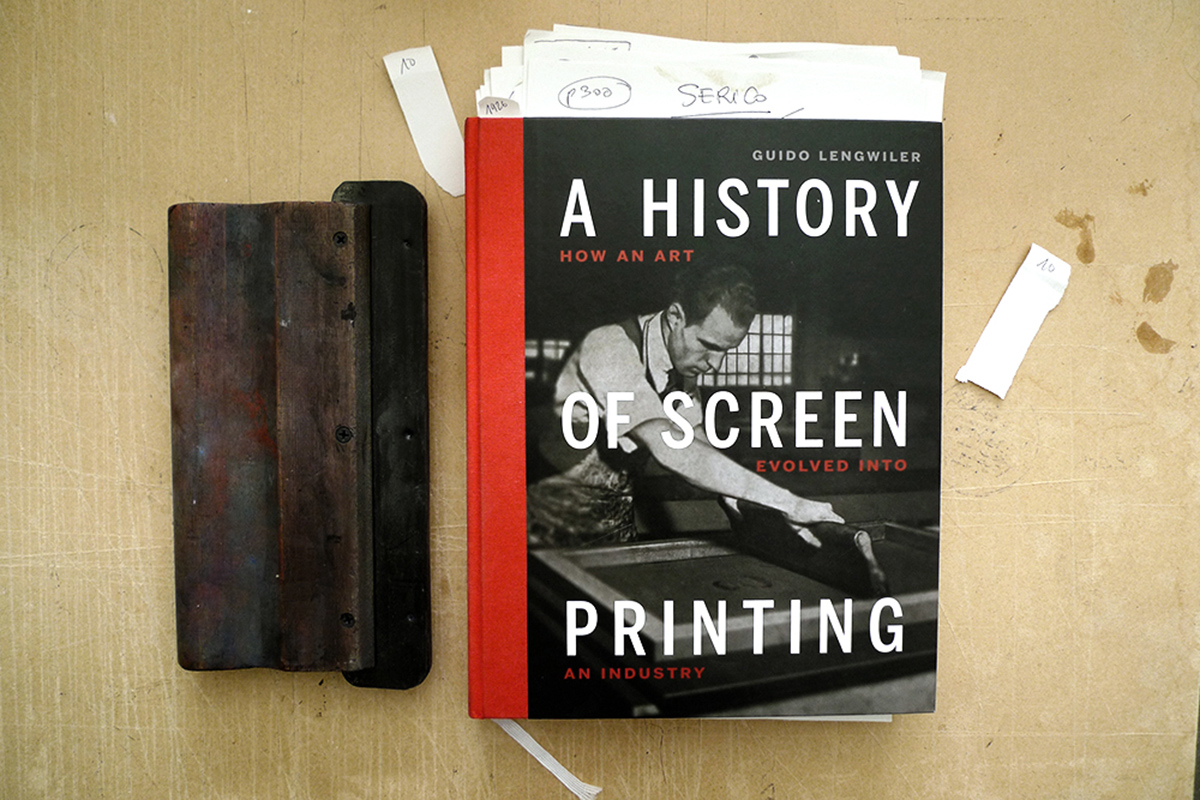

The archives of 15 years of work at Guido Lengwiler’s. All the books are marked with hundreds of bookmarks!

How much time did you dedicate to creating this book, from its conception to its final publication? What financial resources did you have to invest in its production?

I don’t remember exactly. It’s a project that developed gradually and didn’t have a clearly defined framework. I found correspondence dating back to 2001: by that time, the research was already well advanced. I believe everything started around 1998, and investigations into certain details continued right up until just before going to press, at the beginning of 2013.

The research probably cost me more than 50,000 Swiss francs. That might seem like a large amount, but spread over all those years, it actually corresponds to the cost of any normal hobby. However, I can give you some fairly concrete production costs. The majority of the proofreading costs were covered by Kissel+Wolf. I personally paid about 5,000 Swiss francs to complete the work.

A fabulous collection of screen prints belonging to Guido Lengwiler, dated from 1920.

The English translation cost about 12,000 francs. The graphic design and prepress amounted to approximately 23,000 francs, while printing, binding, and shipping costs came to around 70,000 francs. The production costs for the 4,000 books in both German and English were mostly covered by subscriptions from the screen printing industry. I will surely be able to refinance the missing amounts through sales revenue. In the end, if we break even, I’ll be satisfied. If I manage to make a profit on top of that… I certainly won’t say no!

How did you go about your research? What were your sources?

I think this research could be described as “archaeological”: you suddenly find a dinosaur bone and start digging. The more pieces you discover, the better you can imagine what the creature might have looked like. Applied to the field of screen printing, this means that we have now found the key to the creation of this process. However, some aspects will likely remain obscure forever.

One of the many working documents from the Serico archives.

The research began in Switzerland and quickly expanded to England and the United States. The starting point was the company Serico, founded in 1926 and still in existence today. When I worked at Fred Birchler’s as a screen printer, he often told me about his apprenticeship in 1949 at Serico, with the owner at the time, Hans Caspar Ulrich. Since I was interested in that bygone period, I got in touch with the current owner of Serico, Alfred Eich. He had archives from the Ulrich era. Alfred directed me to Ulrich’s son, who passed away in 1950. The family had handwritten notes from Ulrich that contained unique descriptions of the early days of screen printing. In 1927, with the support of Swiss silk gauze manufacturers, Ulrich had traveled to the United States for three months to study the process. The research thus quickly expanded to the United States, as much by chance as by design.

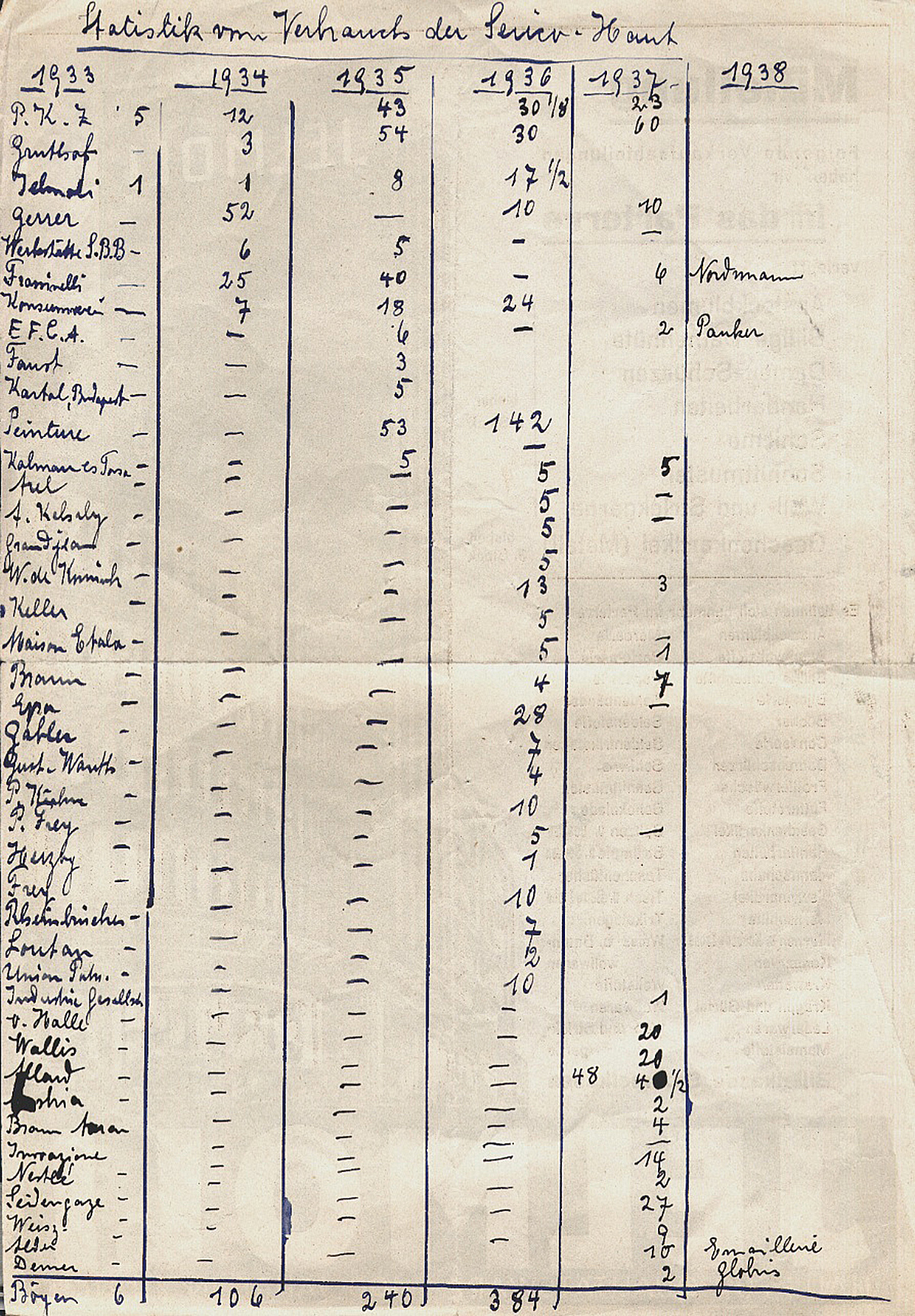

Signs of the Times, one of the very rare copies of this American magazine dedicated to advertising. Here, the June 1924 issue.

Another stroke of luck came when some of the old issues of the American magazine Signs of the Times, covering the period from 1919 to 1950, were put up for sale as used copies. The very first editions of this magazine on advertising techniques and screen printing are extremely rare. So, I bought all the issues for barely 5,000 francs, and I broke into a cold sweat when I received a call from the Basel customs asking where they should send “150 kg of books.” Examining this enormous amount of material then took me two years.

What were the biggest challenges during this material gathering process and while creating the book?

It was difficult to connect all the clues, often fragmented, scattered throughout the Signs of the Times magazine, and to find the main historical thread. But the descriptions of the various pioneers generally align. So, it’s always the same American companies that are mentioned as pioneers by the different authors. And these companies were visited by Ulrich in 1927, where he took detailed notes on the layout of the printing area, the recipes for making stencils, and the inks used.

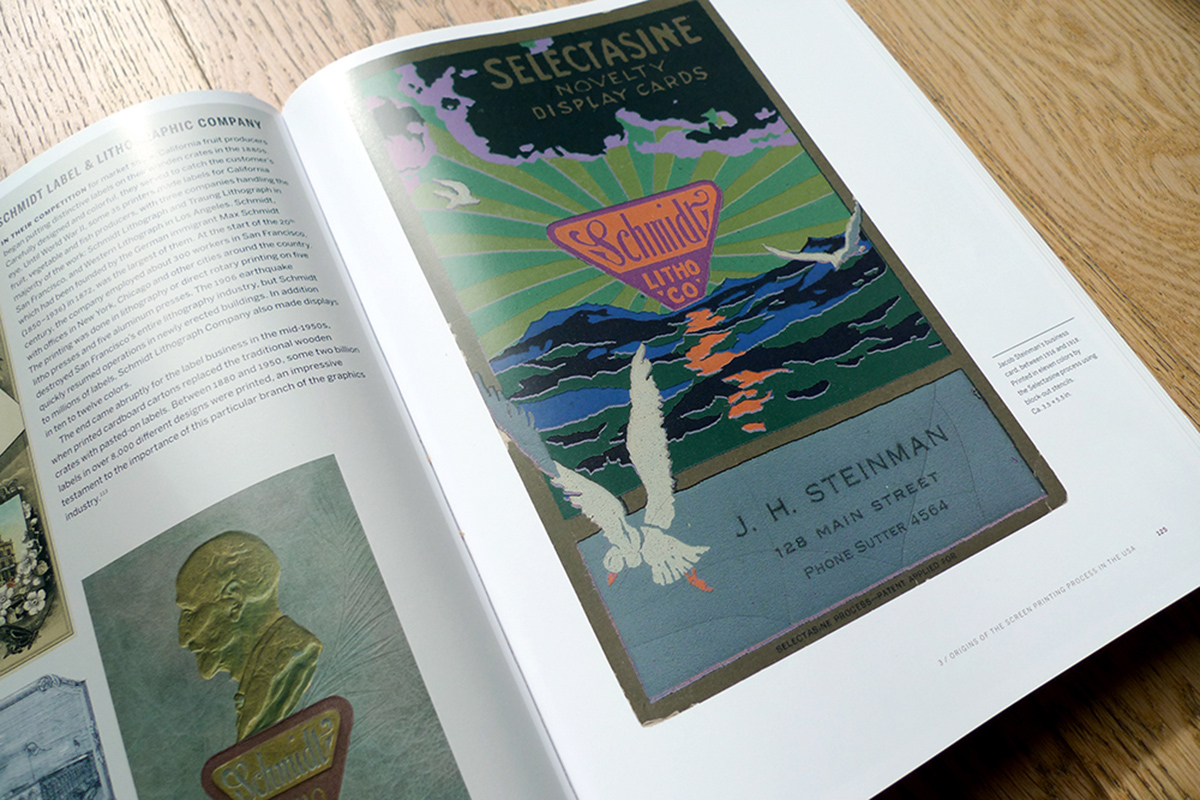

Business card of Jacob Steinman printed in 11 colors using the Selectasine process (between 1916 and 1918).

As part of your research, you contacted many descendants of the international pioneers of screen printing. What were their overall reactions?

Finding descendants of the American pioneers wasn’t easy. It may sound a bit morbid, but I had to purchase copies of the death certificates of these pioneers – over a hundred of these personal documents. These papers list the address of the death witness, usually the widow or one of the children. It took me two years to find a descendant of the pioneer Jacob Steimann, who died in 1933. His daughter had changed her name twice over the years, and the authorities had recorded an incorrect birthdate. The easier cases were resolved within three to six months.

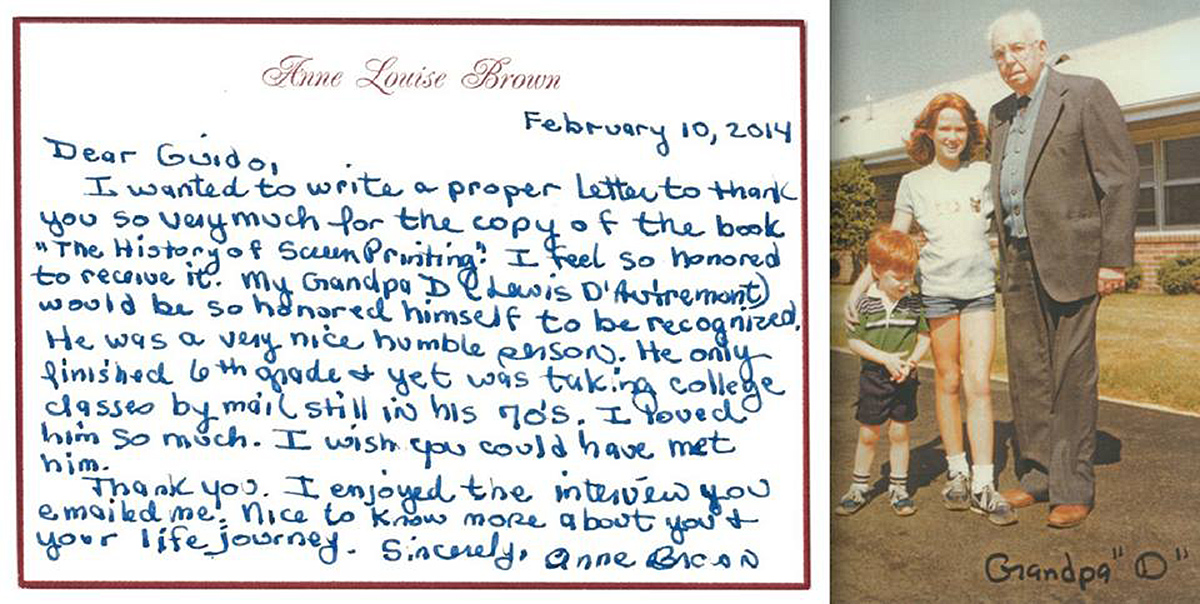

Since the publication of the book, the families of some of the pioneers of screen printing are finally seeing their ancestors receive some recognition. Guido received a letter from Anne Brown, the granddaughter of Louis d’Autremont, the inventor of the stencil film for screen printing.

The families were very helpful, even though they didn’t know me. To this day, I have never been to the United States. Some families had a very rich archival heritage, while others only had a few photos left. In other cases, it was quite the opposite: I knew more than the family did, and I naturally made my documents available to them. In this way, I established many sincere contacts, some of which even turned into friendships.

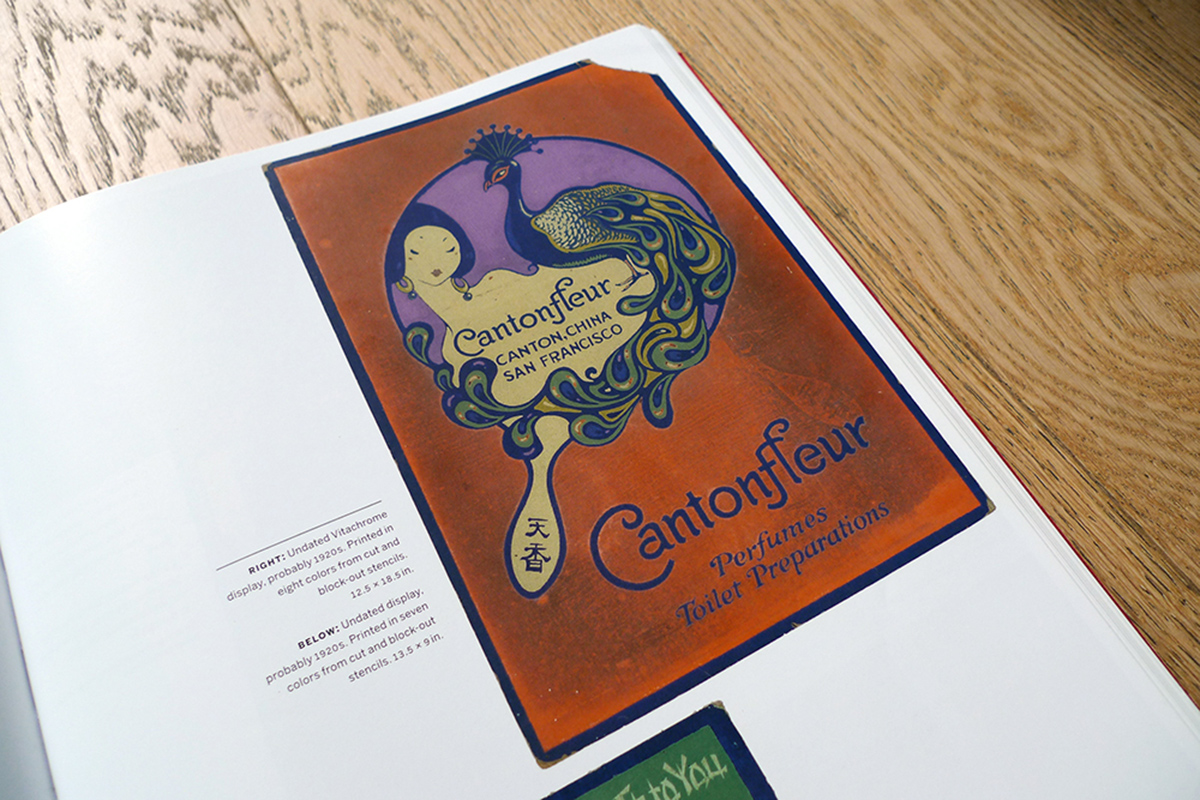

Advertisement by Vitachrome (Los Angeles, USA, 1920).

As part of your research, were there any aspects of the history of screen printing that surprised you?

Yes, I was particularly surprised by the fact that, when graphic applications of screen printing emerged around 1915 in San Francisco, the local lithographic industry invested in and strongly encouraged this new process. Screen printing was thus integrated very early into the graphic arts industry. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that the emergence of the process cannot be considered independent of the political and economic development of the time. The aftermath of World War I was much harsher in Europe than in the United States. America quickly recovered from the war, and the economy was once again growing rapidly in the 1920s – until the stock market crash in 1929.

The screen printing process was still in its early stages in Europe when the global economic crisis hit the continent, whereas in the United States, the method, being more mature, was less affected by the recession. Thanks to its flexibility and low cost, screen printing even benefited from the crisis, finding new areas of expression, particularly in the textile industry and in art.

Are there any parts of your book that you are particularly “proud” of?

Not really. But the first reactions from America have been about the chapters covering Europe. These have apparently impressed readers a lot… The descriptions by Hans Caspar Ulrich clearly resonated deeply with the audience. Ulrich really struggled with the process, but it just wouldn’t work as expected. The timing wasn’t right.

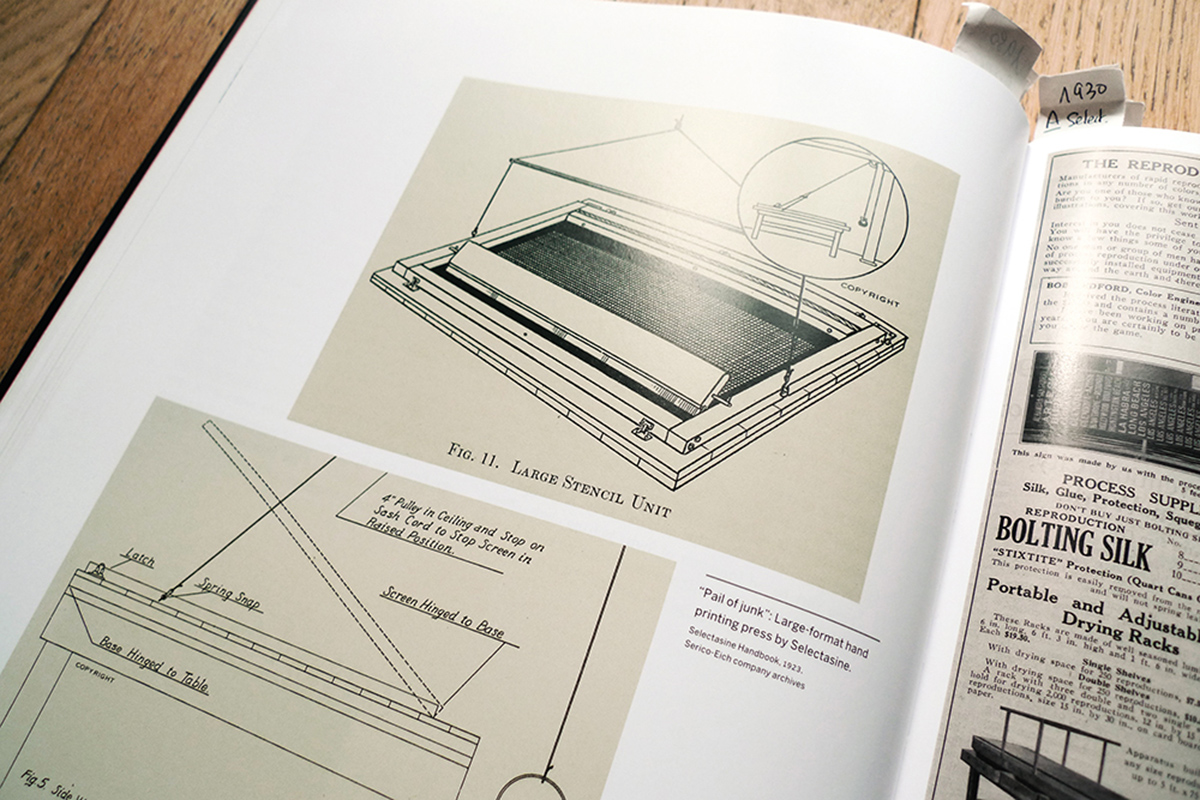

Manual printing frame by Selectasine in 1923 – Serico-Eich archives.

Selectasine had patented a special stencil technique, developed the first screen printing machines, and sold licenses to the graphic industry worldwide. The technique was introduced in Australia and Canada in the years following World War I, and by the second half of the 1920s, it had reached England and mainland Europe. Once again, silk gauze manufacturers and the company Serico played a pioneering role.

The textile industry adopted screen printing in the late 1920s, followed by the ceramics industry half a decade later, and the electronics industry during World War II.

How do you feel now, after all these years dedicated to your work? Are you relieved to have finished it, or do you feel a sense of loss?

Deep down, I always tried to maintain a certain distance from the work in progress. But when the work was finished, I went through a bit of a slump. Ultimately, it was inevitable; I was quite exhausted. But everyone who was involved or collaborated on this publication experienced something similar.

Guido Lengwiler during a screen printing workshop.

How do you see the future of the screen printing process in the fields of graphic design, industry, and technology, respectively?

Hmm… It’s very difficult for me to assess because I don’t have as detailed knowledge of the industrial sector as subcontractors do. From what I’ve heard around me, it seems that in the industrial sector, the process is used in an extremely versatile way and that for many applications, it would be unthinkable to do without it. A colleague from North America visited the screen printing department of aircraft manufacturer Boeing in Seattle a few weeks ago. He summed up his impression in one word: “Giant…”. You can certainly see similar kinds of facilities in Asia.

As for screen printing applied to graphic design, I’ve noticed that over the past ten to fifteen years, the number of training companies and apprentices in Switzerland has decreased by two-thirds – which, in our small country, is almost equivalent to a collapse.

But let’s talk about something else now: Mr. Heinisch, I would like to sincerely thank you for the immense support you’ve given me over the past few years, throughout this extraordinary endeavor. From my perspective, your help was not to be taken for granted…

© 2013 SIP Fachmagazin / Uwe Heinisch

Photos from the book and workshop reproduced with the permission of Guido Lengwiler / all rights reserved / © Dezzig

A History of Screen Printing: How an Art Evolved into an Industry by Guido Lengwiler, published by ST Media Group, Cincinnati. The English version is available on the Squeegeeville website (Canada). The original German version is available on the Niggli Verlag website in Switzerland.