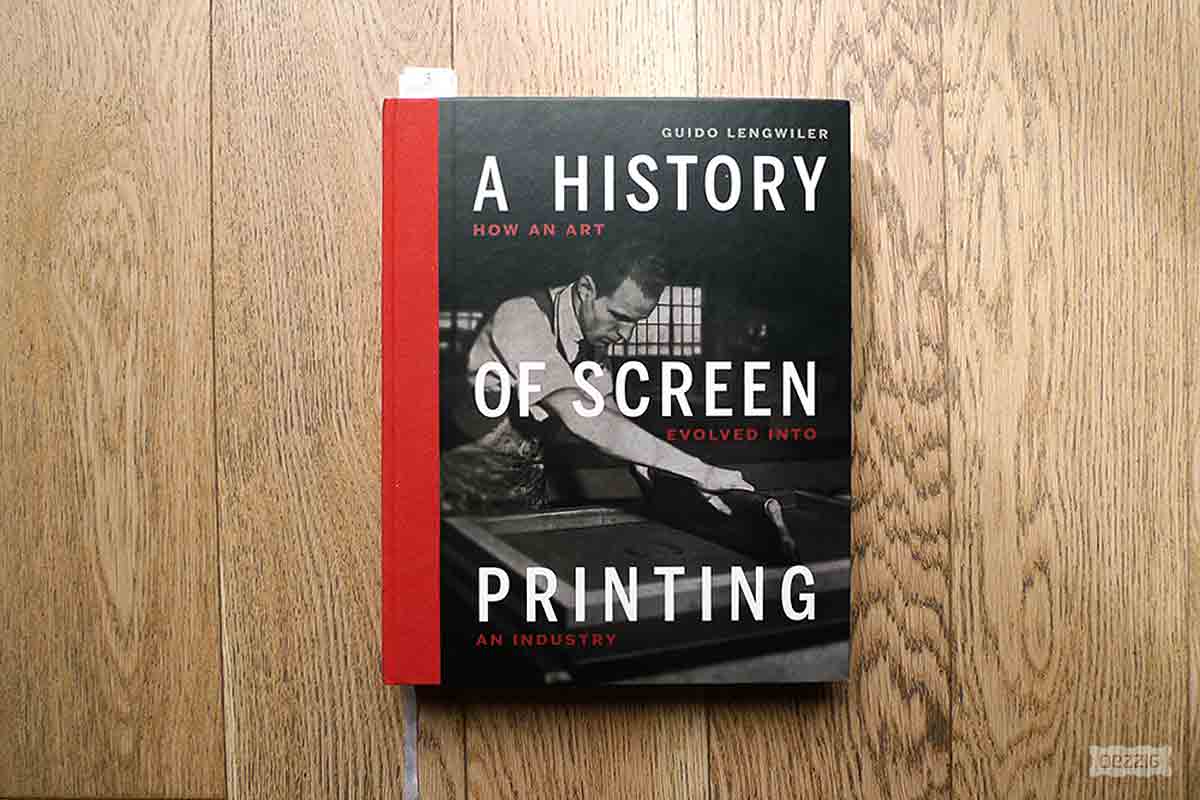

Guido Lengwiler’s book A History of Screen Printing: How an Art Evolved into an Industry traces the development of screen printing up to 1950, richly illustrated with rare photographs. During World War II, the war effort significantly boosted the practice. Yet, by the end of the conflict, screen printing—once thriving in the U.S.—seemed to fall into obscurity. A new era was about to begin…

Unpublished photo: Military screen printing workshop at Fort Sam Houston, San Antonio, Texas – USA, 1943.

World War II: the height of screen printing

“Anyone can make a poster” – this is how the U.S. Army presented the instruction booklets of the Graphic Division of the Office of War Information. During World War II, soldiers were extensively trained to screen print decals or markings for camps and vehicles. And much more: maps, flags, instructions, insignia, propaganda… Even fluorescent and luminescent inks were used for printing maps. These special inks were made from hazardous radioactive elements (like radium), whose use would have consequences…

Printing military markings – U.S. Army base in southern France. Published in Signs of The Times in January 1945.

The war effort significantly boosted the practice of screen printing. Across all conflict zones worldwide, including on Guadalcanal Island, Sign shops were established. These small workshops produced signs and signage for the military. In 1942, the U.S. Army set up the largest screen printing workshop near Baltimore in Aberdeen (USA). Every day, 70 men and 50 women (military and civilian staff) printed over 500 posters and instructional charts.

During this period, advertising activities almost entirely disappeared as screen printing was widely used in Europe to support the war effort (even in Germany). In England, to combat shortages, printed paper was ‘erased’! Surprisingly, in 1940, the Selectasine printing company in London proposed using screen printing to recycle paper by covering it with white ink!

In Guido Lengwiler’s book, there are surprising anecdotes, such as the Dutch screen printer who printed anti-Nazi texts on tiles! These decorative tiles, sold in stores, went unnoticed and fooled the occupiers. Simple messages were inscribed on them (e.g., ‘Every cloud has a silver lining’). They helped the population maintain hope… while the printer kept his business running.

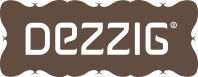

Propaganda poster printed by WPA Poster in 1941 © Library of Congress.

Screen printing strikes back

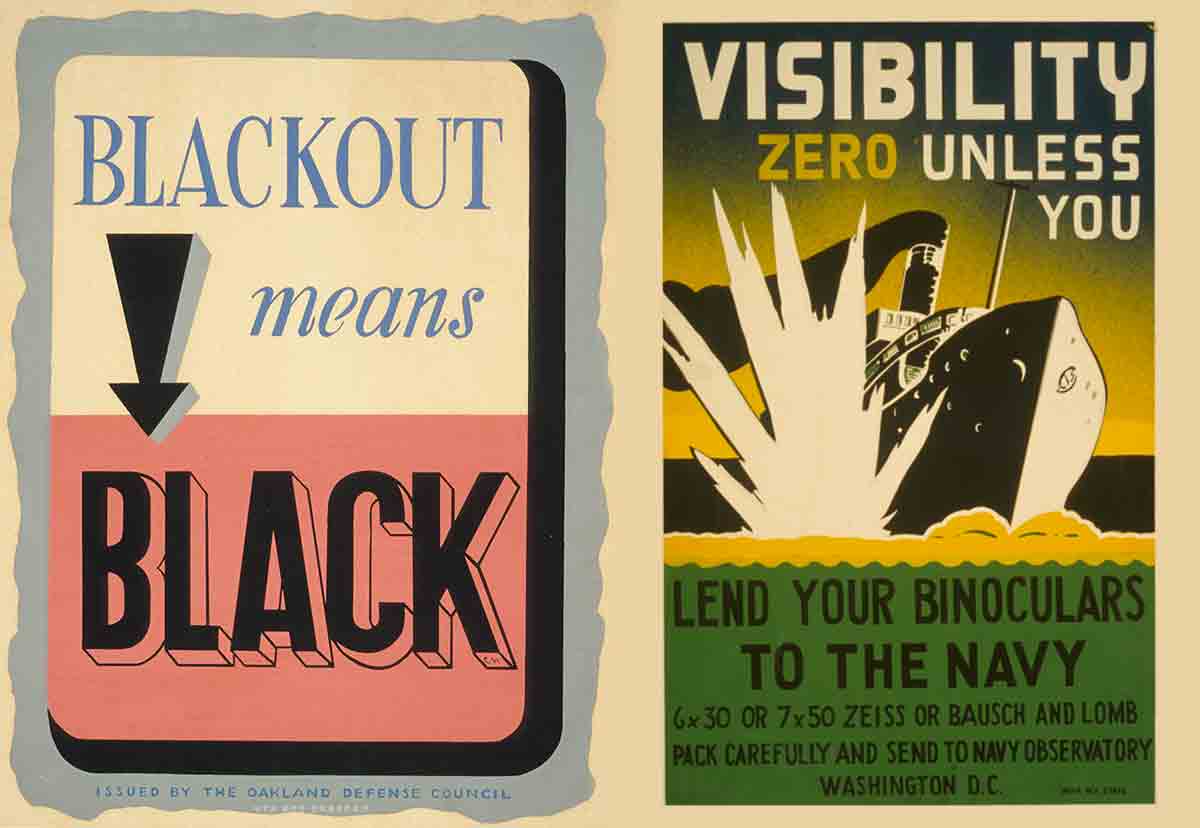

The vast majority of posters produced during World War II by the U.S. Government Printing Office were lithographed. However, many posters from the Americas (Canada, USA, etc.) were screen printed. Starting in 1940, ink and material shortages became critical. Yet, the Army, WPA workshops, and Bryan-Elliott in New York continued to produce striking propaganda posters. Designed by the best advertising artists, these vibrant posters created a desperate but effective campaign, making it seem like the Allies were winning on all fronts, even when that wasn’t always true.

Meanwhile, in 1939, in London, the famous British poster Keep calm & carry on was printed for the Ministry of Information. But don’t be fooled: the original poster was lithographed. A batch of 15 authentic posters was even discovered in 2012. It would take several decades before screen printed reproductions appeared.

Screen printing of American propaganda posters at Bryan-Elliott Cie, New York – 1941.

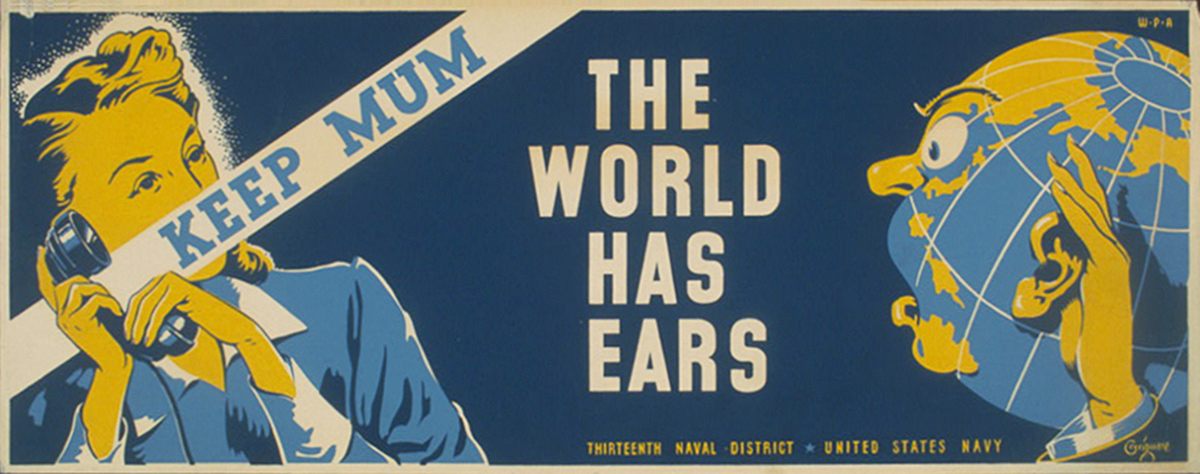

Propaganda poster screen printed by WPA Poster in 1941 / © Library of Congress.

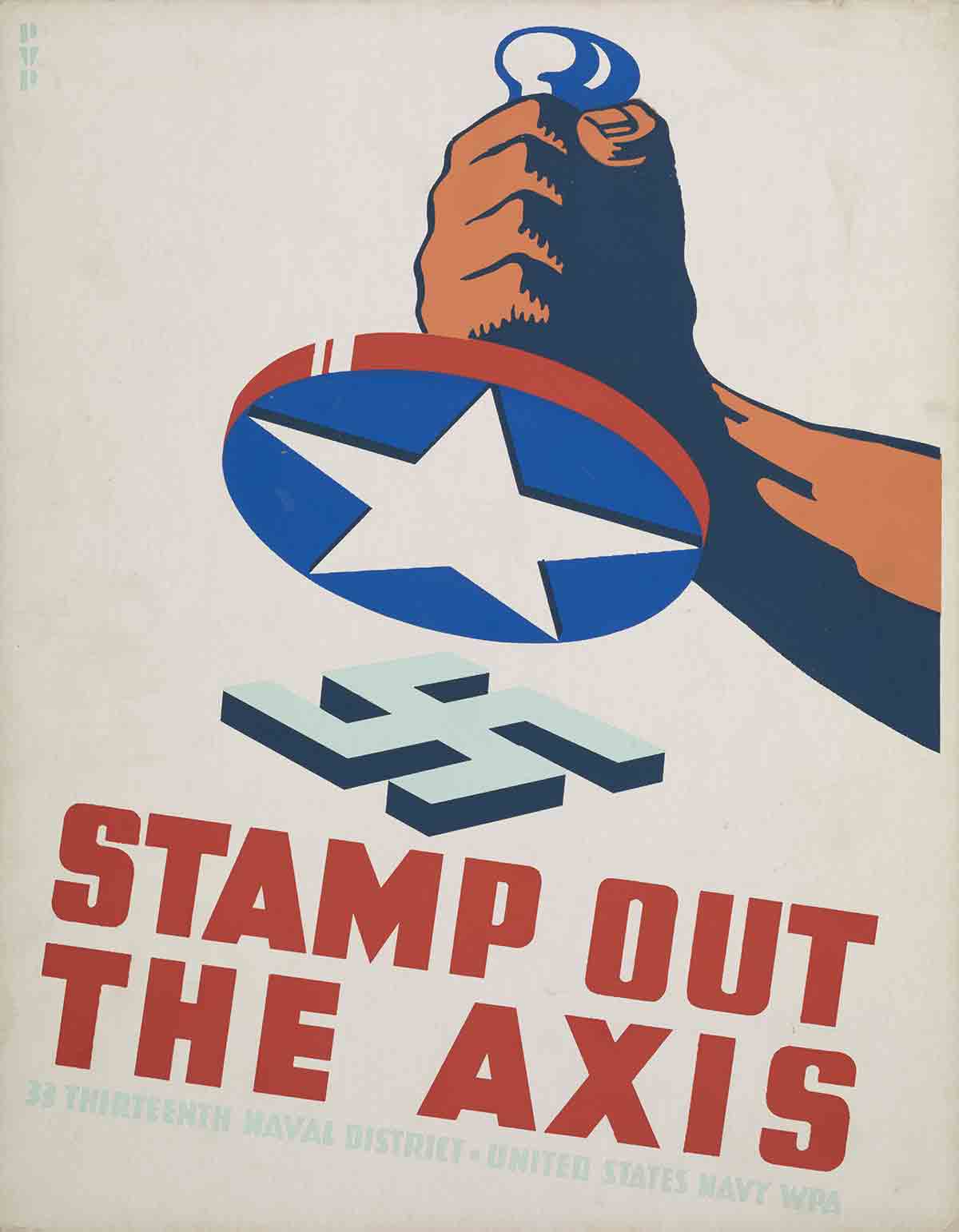

Propaganda poster – WPA Poster, 1942 screen print in 4 colors. Oakland Defense Council, WPA Art Program.

Less known, English artist Victor Hicks was a specialist in propaganda. In 1943, at his studio The Pendock Hicks Co, Ltd in London, he created and printed many posters, some of which were screen printed. These warnings, displayed in workplaces (on canteen or restroom walls), captured workers’ attention. Hicks’ posters were deliberately popular, using simple language and amusing wordplay with a distinctly ‘British’ touch.

Victor Hicks, original 2-color screenprint by Pendock Hicks

The end of the global conflict, however, led to a sudden halt in the development of screen printing in Europe. Almost nothing remained, as if everything had been erased. To be reborn from its ashes, the process would have to be reintroduced from the United States and Great Britain. In Germany, printing presses were destroyed, and the pioneers of screen printing disappeared.

“When the war ended, an entire set of silk screen equipment was abandoned, and one could find it in army surplus stores or with second-hand dealers who didn’t know what to do with it”(Igor Pruzan – L’Écran de Soie). Screen printing then fell into obscurity. In 1948, it was even said to be completely unknown! This marked a new beginning, primarily directed towards industrial use: decals, printing on glass, ceramics, textiles, etc.

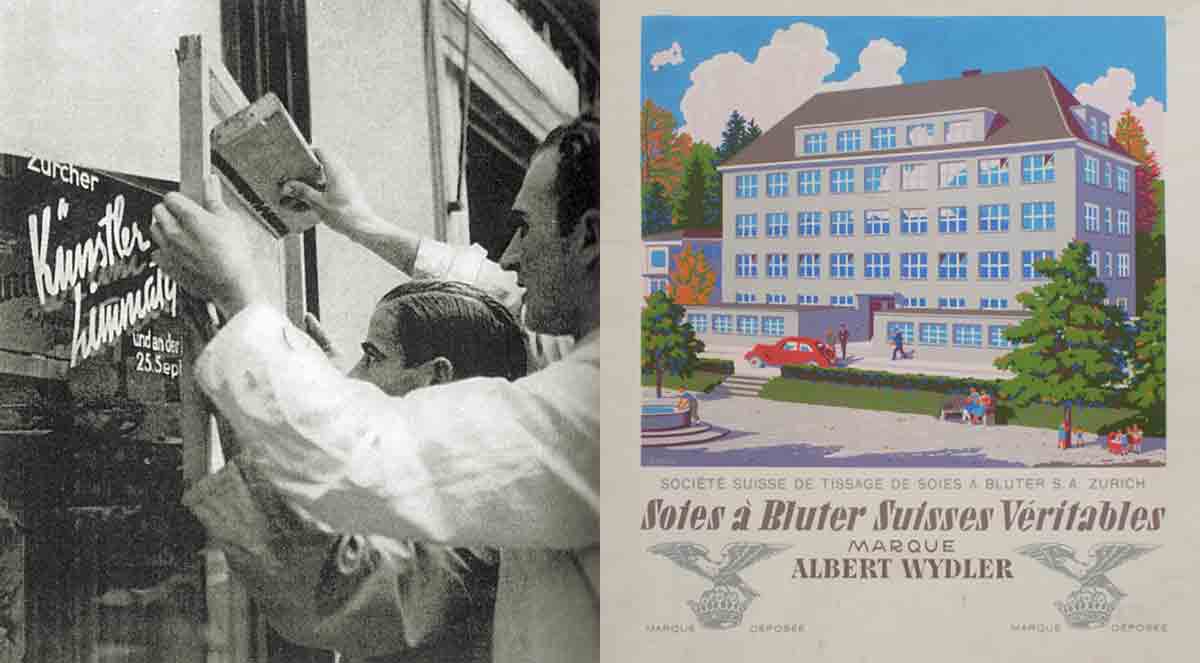

Starting in the 1930s in Switzerland, screen printing began to replace traditional sign painters. Right: 12-color screen printed advertisement © Serico company archives.

Europe: the lost story

Screen printing is wildly popular in the United States—but what about Europe? Surprisingly little, it seems. No evidence of commercial screen printing has been found before 1914. And yet, Switzerland would go on to become a world leader in the field. More precisely, the renowned Serico factory (still active today) became the global leader in silk screen production in 1926. According to Guido Lengwiler’s book, Serico’s company archives and client lists confirm that screen printing was already used in France in the 1930s (first in the textile industry, then in graphic printing). Later, after Robert Eich acquired the company in 1950, Serico likely became the first in Europe to screen print advertising posters.

The Selectasine screen printing process was imported to London from 1925 onward and gradually spread across Northern Europe, often as a complement to traditional printing methods. In the 1920s, documentation and equipment for screen printing were extremely scarce. The technique remained so secretive that in Berlin, Kodloff and Biegeleisen essentially reinvented it under the name Siebdruck. Soon after, in France, Italy, and Switzerland, screen printing was quietly used to apply lettering to shop windows (vitrophanie). From the 1930s, enamel sign manufacturers and the textile industry also adopted the process.

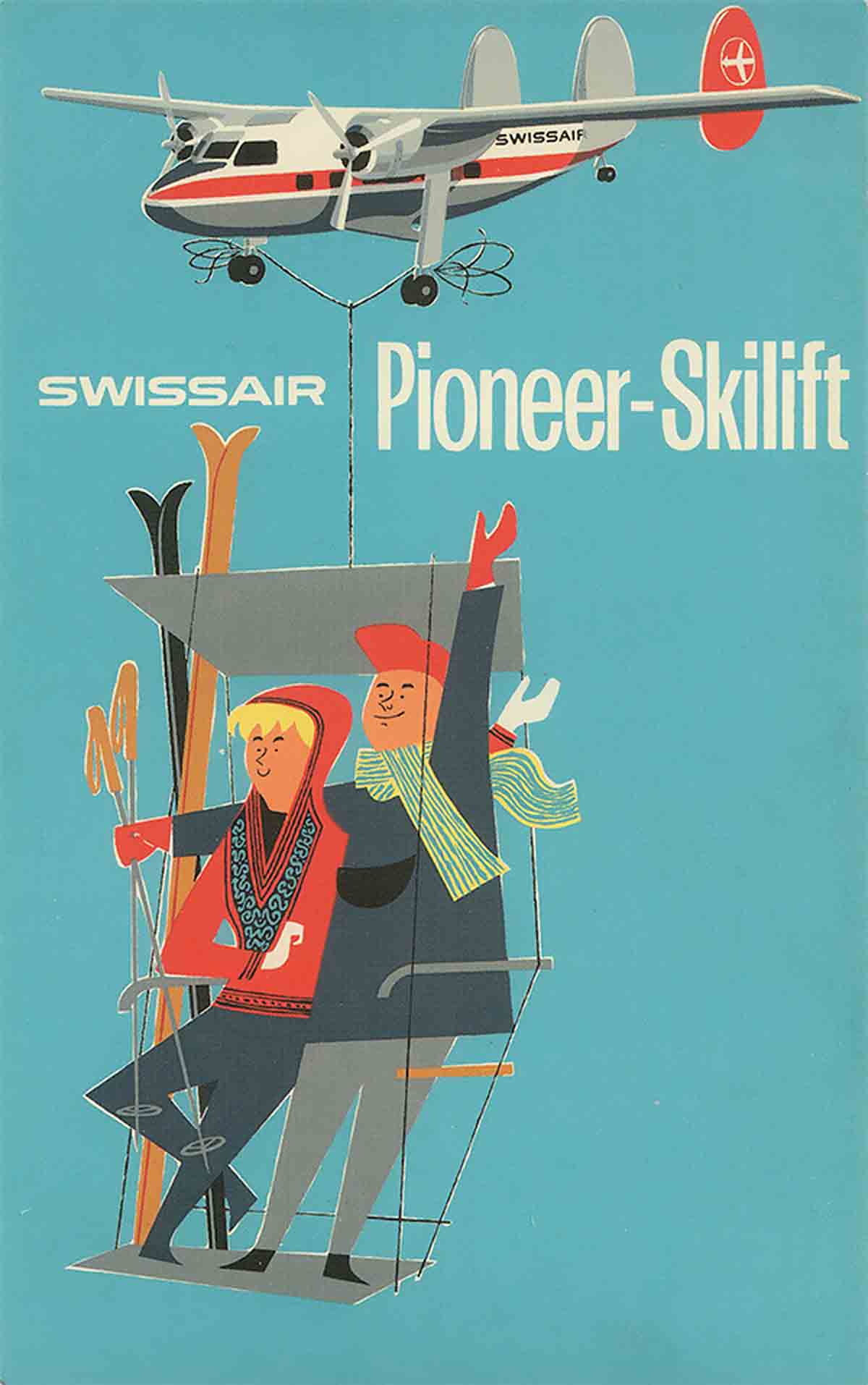

Swissair screenprint poster in 10 colors in the 1950s

© Serico-Eich / Serico Cie archives

Screen printing in France… a different path

As early as the 1920s, fabric screen printing began to gain popularity in France. The process allowed for more refined colors and patterns than the faster method of roller printing. Though production was slower and more limited in volume, it met the high standards of haute couture. Textiles labeled ‘hand-painted’ or ‘hand-printed,’ often seen on scarves or ties, were usually created using stencils.

Later on, in the United States and Canada, screen printing became widely used in 1950s advertising. At the same time, poster production was booming in France—bright, colorful, playful posters were everywhere! Major poster artists like Raymond Savignac, Bernard Villemot, and Gruau worked exclusively with lithographic printing. Since the end of the war, screen printing on paper had been almost entirely abandoned in Europe, slipping once again into obscurity.

1949, screenprint by Silvano Bozzolini © Drouot, Ader Nordmann

More than ten years after the first Serigraphs exhibition that brought recognition to artist Guy MacCoy (Contemporary Art Gallery – 1938), screen printing—despite being acknowledged as a legitimate art form in the United States—struggled to gain a foothold in France.

In the greatest discretion, it wasn’t until the emergence of the CoBrA movement (1948–1952) and its connection to popular traditions that the first artists in France began to take an interest in this technique. Associated with modern art and abstraction, art screen printing distanced itself from the advertising style of major poster artists.

The Italian painter Silvano Bozzolini moved to Paris and, starting in 1949, began producing printed works using a combination of stencil and screen printing. He was soon followed, from 1950 onward, by Picasso and then Fernand Léger, whose screen prints were produced by Jean Bruller (also known as Vercors, the writer). “Fernand Léger examined the gouache he had brought back, remarking that he hadn’t damaged it. He had the same surprised reaction we did when learning the piece he held was merely a callichromie (screenprint) by Vercors.” Henri Goetz par lui-même, Les Cahiers du Musée National d’Art Moderne, 1982, Centre Georges Pompidou.

Denise René in the 1950s © Odense Bys Museer

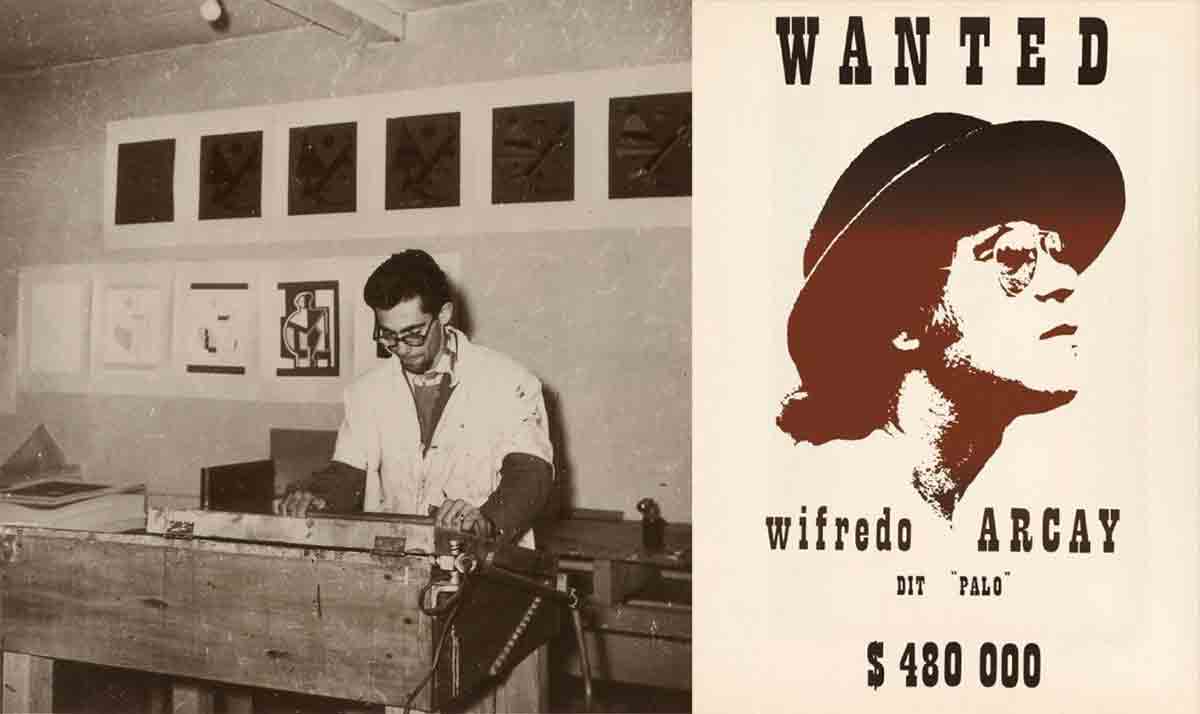

Wifredo Arcay in his workshop in Meudon in 1953. On the right: 1-color screenprint.

Although it wasn’t until 1968 that art screen printing became popular, André Girard from the Collège Estienne gave a presentation on it as early as 1951. In 1954, the Galerie Denise René, in Saint-Germain (Paris) showcased a portfolio of screen prints produced by the Arcay Studio, featuring artists like Vasarely, Poliakoff, Bozzolini, and others. Wifredo Arcay, born in Havana in 1925, arrived in Paris in 1949, where he founded his screen printing studio in 1951.

Art screen printing in France also has its forgotten pioneers… It is a new history that remains to be written..

The book A History of Screen Printing: How an Art Evolved into an Industry is a puzzle in which one must know how to lose oneself: portraits, workshop photos, machines, reproductions of printed works, facsimiles of technical manuals or patents. This is the great strength of this major book: the testimonies and portraits prioritize the human aspect, bringing the artistic practice to life.

Screen printing is a particularly fundamental technique in the United States. From its beginnings, it was a true art, alongside its use in advertising. The book focuses very little on European countries, where screen printing was still in its infancy. California remains, more than ever, the birthplace of graphic art screen printing. This is where the history of sérigraphics truly begins.

“Screen printing is a revolution for graphic art…”

Harry Stenberg (1904–2001)

A lire aussi :

Guido Lengwiler on the making of his screen printing book

The hidden story of screen printing 1/3: the pioneers

The hidden story of screen printing 2/3: a golden age of graphic art

The translated excerpts and photographs from the book are reproduced with the permission of Guido Lengwiler A History of Screen Printing: How an Art Evolved into an Industry

All rights reserved / Photos © 2014 Dezzig.